PAPERBACK; 182 P. TRANS. LOLA ROGERS SERPENT'S TAIL, 2014/2011 SOURCE: LIBRARY

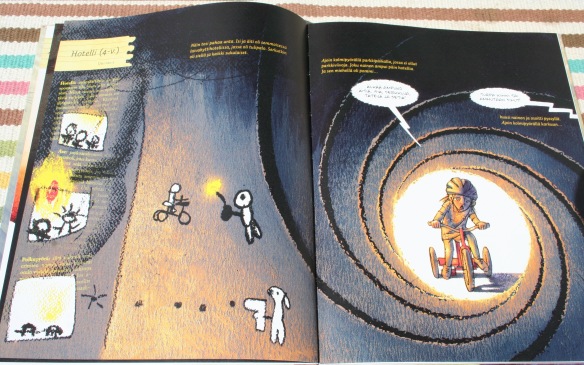

A sad young Finnish woman boards a train in Moscow, in the waning years of the Soviet Union. Bound for Mongolia, she’s trying to put as much space as possible between her and a broken relationship. Wanting to be alone, she chooses an empty compartment—No. 6.—but her solitude is soon shattered by the arrival of a fellow passenger: Vadim Nikolayevich Ivanov, a grizzled, opinionated, foul-mouthed former soldier. Vadim fills the compartment with his long and colorful stories, recounting in lurid detail his sexual conquests and violent fights.

There is a hint of menace in the air, but initially the woman is not so much scared of or shocked by him as she is repulsed. She stands up to him, throwing a boot at his head. But though Vadim may be crude, he isn’t cruel, and he shares with her the sausage and black bread and tea he’s brought for the journey, coaxing the girl out of her silent gloom. As their train cuts slowly across thousands of miles of a wintry Russia, where “everything is in motion, snow, water, air, trees, clouds, wind, cities, villages, people and thoughts,” a grudging kind of companionship grows between the two inhabitants of Compartment No. 6. When they finally arrive in Ulan Bator, a series of starlit and sinister encounters bring this incantatory story about a ruined but beautiful country to its powerful conclusion.

Compartment no. 6 is a fantastic novel about travelling – the odd kinship formed between complete strangers – and about Soviet Russia. It begins with the boarding of the Trans-Siberian train, in which a young Finnish student finds herself sharing a train compartment with a boorish Russian construction worker. The girl is looking for an escape from her current situation, because she feels trapped and unable to make up her mind about her relationship with a young man she cares for. Hoping to enjoy the peace and quiet of the Siberian nature and to shut herself from the world, she is, however, forced to come into contact with the brazen, oversharing comrade.

The beauty of the novel lies in the way in which it describes movement. Liksom’s writing is so vivid and compelling that I could almost see the landscape flashing in the train window with my very own eyes – all from the comfort of my comfy couch and centrally heated apartment. I guess it is no wonder that Liksom chose to set the novel during the freezing winter season, as it emphasises the desperation to live and the yearning to die inherent in the nation. The apathy and passion, the poverty and garish luxury – the Soviet Union drawn in Compartment no. 6 is full of contradictions. Even the most despicable travel companion somehow becomes endearing in closed confinement.

Although the many of the details have faded away in the months after reading this novel, Compartment no. 6 is one that still occasionally comes back to haunt me. Although at first it might seem slightly underwhelming in action, the novel leaves a lasting impression. The rhythm of the narration, the pulse of the train on the tracks, feels alive, and the depiction of Soviet Russia as both abhorrent and intriguing is almost loving. There is much to despise in the swearing, uneducated, misogynic male character, but yet there is also the hint of honesty and raw humanity that’s been stripped back to its basest form. So what is the novel really about? In my opinion it’s about two people, two worlds coming together in a closed space; the contact is unavoidable, and though the situation feels occasionally very claustrophobic, there is also much to learn by listening and opening up to these discussions.

I very much enjoyed Compartment no. 6, and I’m glad that it has been translated into several languages and thus has found (and hopefully charmed) readers across the world. If you do ever come across a copy of this book, I urge you to pick it up and read it. For such a short novel it provides fascinating insight to human relationships. I’d especially recommend this to readers who are planning to or have travelled the Trans-Siberian railway or are interested in Soviet fiction in general. If you want more convincing, I suggest you read also Sarah’s and Madame Bibi’s fantastic reviews.

4/5

An unknown Russia frozen in ice opens up ahead, the train speeds onward, shining stars etched against a tired sky, the train plunging into nature, into oppressive darkness lit by a cloudy, starless sky. Everything is in motion: snow, water, air, trees, clouds, wind, cities, villages, people, thoughts.